In GLOSSY 2 the photographs included have all been produced in our own century and the exhibition showcases the work of seven photographers – working in Australia, or Australians working overseas – who have contributed extensively to the world of magazines. The exhibition shares with its predecessor the idea that the prints displayed in the Gallery are a part of a process – a process whose endpoint is found in the pages of magazines.

The past five years have witnessed a significant shift from film to digital among professional photographers. There have been significant technical advances in magazine production, albeit none as revolutionary as the move to camera-ready typography that created a new freedom for magazine art directors in the late 1960s (which the National Portrait Gallery celebrated in the 2002 exhibition POL: portrait of a generation.) Despite the steady growth of the Internet, magazines and magazine culture show no signs of decline. Indeed glossy inserts with newspapers have become more elaborate; production values are higher and these inserts are now a regular source of opportunity for considered essays in portrait photography.

GLOSSY 2 has been selected to highlight the distinctive and individual approaches of the photographers. The exhibition displays something of the range of photographic portraiture to be found in contemporary magazines. While it is impossible to mount an exhibition which encompasses the complete range of attitudes found in magazine culture, it is possible to perceive some trends. The convergence between the worlds of portraiture, fashion, celebrity, notoriety and music, a matrix that has been a feature of magazines since the 1980s, continues to set the context of the work in this exhibition.

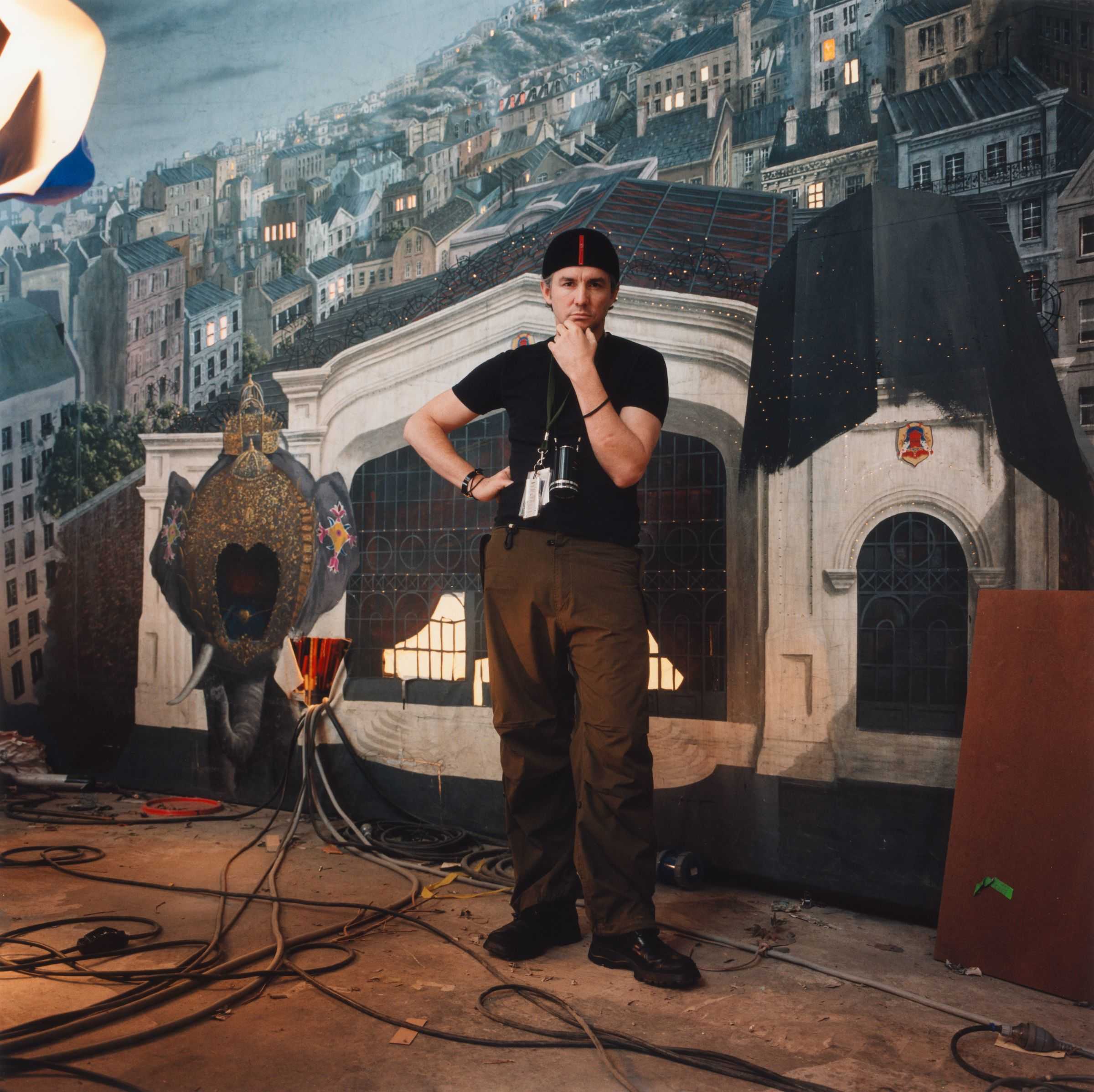

Photographers who work for magazines are often called upon to create images in very compressed timeframes. The demand to produce a searching portrait image, sometimes in as little as a few minutes, is a particular and constant pressure on the photographer. In such circumstances the possibilities of setting are often crucial in creating a successful portrait. Each of the photographers in GLOSSY 2 has developed a sure eye for setting. Invar Kenne, for example sets woodblock printmaker Cressida Campbell standing before the backdrop of the distressed wooden boards of a suburban house.

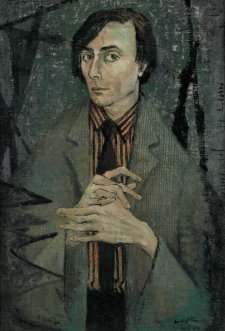

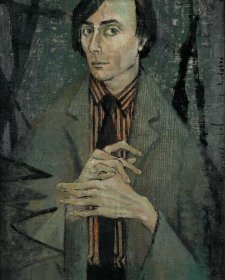

In his photograph of Keno Hernandez, Sahlan Hayes creates a characteristically umbrous work in which the spatial arrangements are highly complex, not easy to read at first glance. It is perhaps no accident that in this exhibition Hayes is represented with two photographs of painters, Charles Blackman and Jeffrey Smart. The painterly quality of his work is a reminder that the photographer's vision and the painter's vision, too, are in a constant state of convergence.

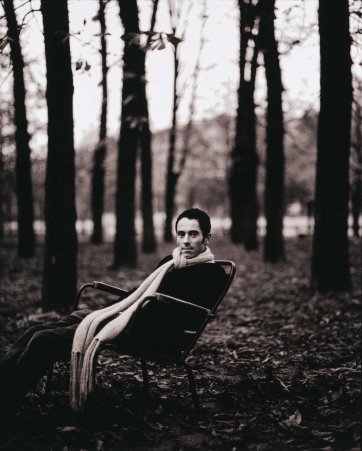

While photographers for magazines now prefer colour, the photographers included in this exhibition slide easily between colour and portraits conceived in black-and-white. While in general the 20th century will always be the century defined in black-and-white and the 21st century is being recorded in colour, the possibilities of strength and distillation inherent in the monochrome medium continue to be exploited by photographers such as Julian Kingma. It is impossible to imagine his moody portrait of Robert Dessaix with its mantilla of lachrymose branches, rendered in colour.

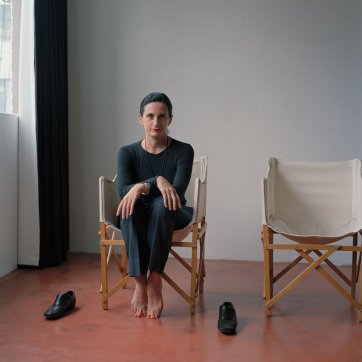

While much magazine photography aims at naturalism, there is an equally strong devotion to the constructed and the artificial. Ellen Dahl has paid tribute to the specific qualities of the natural light in Australia, yet in her work and in that of Daniela Federici there are few concessions to the world outside the studio. Both photographers revel in the flawless perfection of controlled studio lighting and in the almost impossibly pure complexions of their subjects. In their work, as in the work of Christopher Morris, the divide between fashion and portraiture is not easily found. There is another form of convergence between art and photography in operation, too, in the photographer's role of icon creation.

Portrait photographers whose work is included in magazines not only create, but confirm the public presence of their subjects. Many of the subjects included in GLOSSY 2 have been photographed many times; they are aware of what the camera can do and how to compose themselves for the lens. In an environment of controlled imagery it is the challenge of the photographer to dance with the subject to create an original view. A classic technique, used to great effect by Ben Baker, is to come in close and to bring the subject into an uncomfortable proximity – this technique to get behind the mask creates what is quite literally an "in your face" expression of the subjects’ dominant places in the world. This is a particularly effective technique for a photographer whose subjects include some of the most powerful men and women in the United States - Rupert Murdoch and former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani are two examples.

Photography for magazines shares with the genre in general a concern with the temporal world. All of the photographers in the exhibition deal with the passing of time in subtly different ways. Ingvar Kenne’s portraits of Michael Chaney and Collette Dinnigan include multiple views, a kind of photographic Cubism. But for the most part the photographers accept the nature of the craft, to make the most of a tiny fractured moment of time in the lives of their subjects. The currency of magazines is short-lived; fame, celebrity, notoriety, popularity seldom last more than a generation. Yet it is through images, images created by artists whatever their medium, that the collective memory of our age is transmitted into the future.

Andrew Sayers